Russell Wilson has hopped on the insurance train, but the nature of financial protection in football continues to evolve

The legal requirement for drivers to possess motor vehicle insurance is a universally recognized principle, considering the substantial number of accidents that occur annually.

To venture onto the road without it would be a negligent oversight. Similarly, homeowners comprehensively safeguard their properties and belongings through insurance coverage, anticipating potential mishaps like storms, fires, or theft.

The inherent importance of these policies is widely acknowledged.

Interestingly, within the realm of sports, discussions concerning insurance remain notably subdued, despite its far-reaching significance in shaping the sport’s economic landscape.

Amidst this backdrop, a rather overlooked facet emerges – the prominent role that insurance quietly assumes.

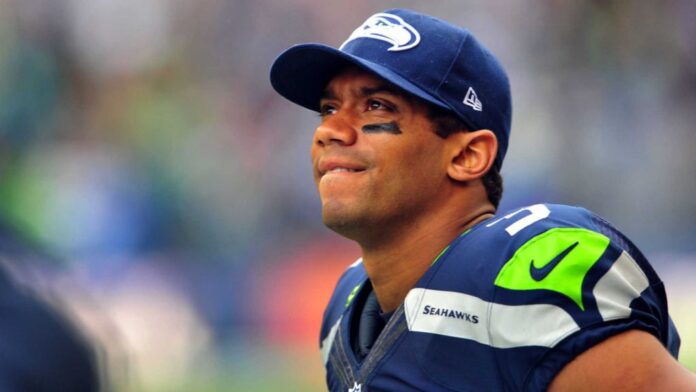

In the midst of contract negotiations that have seemingly reached an impasse between quarterback Russell Wilson and the Seattle Seahawks, a lesser-known development surfaces: Wilson has reportedly taken a significant step by securing an insurance policy specifically tailored to guard against the ramifications of a career-ending injury for the 2015 season.

This decision resonates as an intriguing example of the subtle yet potent role that insurance plays in the dynamic world of professional sports.

Beyond the spotlight, insurance serves as a strategic tool that athletes like Wilson can utilize to mitigate potential career-altering risks.

The extent of its involvement in the intricate economics of the game might often escape public attention, but its influence remains palpable.

Seattle QB Russell Wilson will play last season of his deal w/ insurance policy worth millions in case of career-ending injury, per sources.

— Adam Schefter (@AdamSchefter) June 16, 2015

In football, these policies typically are purchased by collegians projected to play in the NFL. There are two policies for which an athlete can apply: disability and loss of value coverage.

Disability is in case the athlete sustains a career-ending injury and can never play the sport again.

Loss of value refers to an athlete’s loss in projected value due to an injury, yet the player is still able to compete. Here are two examples from my personal experience to illustrate the differences in these policies:

The NCAA started the Exceptional Student-Athlete Disability Insurance Program in 1990 to protect an athlete’s future earnings against a career-ending injury.

This policy is offered with up to $5 million in coverage. The coverage amount depends on the projected value of the athlete.

A projected top 10 NFL pick may receive the maximum value of coverage ($5 million), while a projected third-round pick is offered $500,000.

The reasoning for the NCAA’s involvement in coverage was to prevent agents from providing policies to athletes in exchange for the player’s promise to sign with them.

The NCAA offers a loan program at 1 1/2 percent above prime to pay for the policy, although balances must be paid whether or not an athlete is drafted.

It’s estimated that 100 athletes a year participate in the program — 3/4 of which are football players.

Following my sophomore year at Notre Dame (2005) I took out a disability insurance policy that provided a $1 million payout in the event that I was permanently disabled from playing football. The $10,000 premium was paid by my family.

The NCAA program is tedious and requires a decent amount of legwork, so my family and I decided to work with a private insurer who specialized in these matters and provided an open line of communication throughout the process.

Different from the NFL and its non-guaranteed contracts, NBA and NHL teams take out insurance policies on players in the event of an injury.

When I decided to return for my senior season (2006) at Notre Dame, I procured a $14.4 million policy with Lloyd’s of London that projected I would be drafted within the top half of the first round. It also included the standard disability policy in case of a career-ending injury.

The language for the loss of value policy specified that if I dropped out of the top 16 picks due to injury, I would be rewarded the difference between whatever contract I signed and $14.4 million.

This policy was almost identical to the one signed by Matt Leinart, who, the year before, decided to return for his final year of eligibility at USC.

Unfortunately, I paid the hefty premium once I signed my first NFL contract. In retrospect, I should have only taken out the disability insurance instead of including the loss of value policy.

Insurance companies will gladly accept the premiums from players like myself. It’s extremely difficult – not to mention expensive and time-consuming – to collect on loss of value policies. Former USC wide receiver (and current Jacksonville Jaguar) Marqise Lee is now involved in a court battle regarding loss of value policies. More info regarding his potentially landmark case can be found here:

In an effort to provide less risk to future NFL stars, the NCAA has changed its stance on paying premiums for their star athletes.

In a story last year by Bruce Feldman of Fox Sports, Texas A&M took advantage of a newer rule that allows universities to tap into their Student Assistance Fund.

The original intent of this fund was to cover post-eligibility financial aid and travel for students for emergencies or even if they needed a suit to wear to a university function.

The NCAA creates a yearly limit for all schools to budget, and last season’s budget for the Southeastern Conference reportedly was $350,000.

This loophole afforded Texas A&M the opportunity to pay recent first-round pick Cedric Ogbuehi’s premium and allow him the chance to play another year at A&M.

Florida State provided the same financial assistance to Jameis Winston last season for a policy that projected Winston to be a top-10 pick for $8-$10 million.

The premium, which reportedly was $55,000-$60,000, took a large chunk out of the Student Assistance Fund. But the circumstances in which these funds are used are rare at best.

The ability of universities to offer this service is a game changer. It provides star athletes with the financial coverage necessary to fulfill their athletic eligibility while providing them a better chance at a degree.

It also gives programs the opportunity to capitalize off their student-athletes before they relinquish their amateur status.

Different from the NFL and its non-guaranteed contracts, NBA and NHL teams take out insurance policies on players in the event of an injury.

Salaries have skyrocketed over the past few decades, so much so that it has increased the risk involved with signing a star athlete to an extremely lucrative guaranteed contract. That has forced the NBA and NHL to secure affordable rates for temporary coverage with league-wide insurance plans.

By pooling risk, insurers are able to project claims better and can be confident they are not just covering the most injury-prone.

The NBA’s policy, provided by BWD Group, costs a mere 4 percent of salaries, although it is permissible to only the club’s top five players and has limited exclusions for pre-existing injuries (which is standard in every insurance policy).

In the case of Wilson, the disability coverage is a no-brainer, but that may not be the case after he signs a new deal.

Seahawks GM John Schneider previously mentioned an “unconventional contract” for Wilson, which prompted many to believe Wilson could receive the first fully guaranteed contract extension for a QB. Now this seems light years away, given the lack of progress between the sides.

But if or when it does take place, expect other players to follow suit in search of guaranteed contracts.

Wilson’s contract could be ground-breaking not only for players but league economics as a whole. This domino effect would force the NFL to create league-wide insurance plans similar to the NBA and NHL.

Of course, this is all hypothetical and not something the 31 other NFL owners and teams would like to transpire.

But given Wilson’s success in his first three years, it is possible.

Whether the Seahawks want to be the first team to break the ice on fully (or near-fully) guaranteed contracts is yet to be seen, but it’s certain that insurance policies aren’t going away anytime soon, regardless of who carries the risk.

Maybe I need to get into the insurance business…